Natty Gann and the Female Hobo

Whilst looking for something to put on in the background during a washing up marathon the other day, I stumbled across a 1985 Disney film called The Journey of Natty Gann. Set during the Depression of the 1930s, it’s an – inevitably – heartwarming story of a teenage tomboy who gets separated from – also inevitably – her dad, but is befriended by – sigh – a wolf.

Who is Natty Gann?

I’d never heard of the film before – do any of you remember it? Anyway, here’s the trailer: watch out for a super young John Cusack! (I admit that played a part in my decision to watch it. That and the trains.)

Also, someone should tell Natty that her dad is actually Leland Palmer.

A few more feminist points for Disney

The film stars a young Meredith Salenger as Natty, whose understated performance undercuts many of the more saccharine moments of the film. She comes across as tough rather than ‘feisty’, which is a rare treat.

Although all Natty’s major relationships are with male characters (she has the Disney missing mother syndrome) so it definitely doesn’t pass Bechdel, I think the film gets feminist points in other places. Mostly because the lead protagonist, Natty, is so kickass. She’s smart, brave and resourceful. It’s a proper adventure – there’s an epic journey, friends and foes, and very real danger. She escapes various shades of train-related death as she rides the rails to find her father, and she also escapes an orphanage-prison and a sexual assault. She does loads of running.

Natty’s also a tomboy and crucially doesn’t get made over into a “Proper Girl” at any point. My favourite thing is that no one seems to care that she’s dressed like a boy – no one ever mentions it or makes a derogatory comment about it. And she pulls John Cusack while wearing shirt, trews, boots and a flat cap. Love it!

No women wanderers?

Another part of this film’s feminist cred is its rare depiction of a female hobo. From Woody Guthrie to Kerouac to Big Rock Candy Mountain, the figure of the hobo is as much a part of US cultural identity as the cowboy. Both ways of living were at best hard and at worst brutal and dehumanising but have been romanticized and over the years have passed into folklore. And like cowboys, maybe even more so, hobos are almost exclusively imagined and represented as being male.

Perhaps the greatest lesson that has come from the active study of the history of marginalised social groups is that even where it’s not recorded that they were there, they were. Ethnic minorities, women, refugees, people with disabilities, people with a dazzling range of sexual orientations, gender identities and expressions… no group just popped into being in the 1980s. So hopefully it will come as no surprise that there were women hobos, and plenty of them.

In January 1934’s US census, nearly 14,500 women were recorded as homeless or transient, nearly 2,783 of them under 21. A 1906 estimate put the total hobo population of the US at 500,000, but numbers increased dramatically during the Great Depression as homelessness spiralled to an estimated two million.

There are a few firsthand accounts from women hobos, such as this one from Norma Darrah. The most famous record comes from ‘Boxcar’ Bertha Thompson, although it was later revealed that her autobiography, Sister of the Road, was a fictionalized account stitched together from the experiences of several different women. Rather unbelievably, the story inspired Martin Scorsese and producer Roger Corman to make a ridiculous hobo-themed sexploitation flick:

Amazing. (I look forward to the sequel – a rootin’ tootin’ sexy romp about Bob Dylan’s boxcar days.)

Riding the rails of patriarchy

Like Natty, many women and girls who were wandering would dress as men, for comfort and camaraderie but also for protection since – like homeless women today – they were especially vulnerable to sexual violence. Many hobo women had transactional sex to help secure food, money and passage.

Perhaps it’s this detail in particular which has helped to shut the female hobo out of the golden halls of myth and folklore. The reality of many women’s experiences was harder to romanticize than that of their male counterparts, and the fact that many were sexually exploited undermined the charming hobo ‘ethical code‘ drawn up in 1889. I suspect it’s also to do with our old chums gender stereotypes and double standards – take a bow, fellas!

The urge to roam, the ‘wanderlust’ which is so highly prized in narratives of American identity, is usually held to be incompatible with femininity or femaleness. Where a man who roams and values his independence is admired, the same traits in a woman are often characterised as fickleness or infidelity.

In a culture and at a time when women were inextricably linked to the private sphere of domesticity, and were called upon – imaginatively or actually – to represent and defend ‘home sweet home’, the homeless female wanderer is an unsettling figure. She has rejected her assigned role and slipped into the great blue yonder, claiming her right to agency and mobility despite the cost.

POSTSCRIPT: As part of my research for this post, I tried to do a quick twitter poll to see how many people remembered seeing The Journey of Natty Gann as a child, and whether it had contributed to them becoming a feminist. I didn’t really get any response apart from this one, but it made me very happy indeed.

Things to read!

- In Search of the Female Hobo, essay by Heather Tapley

- Joan M. Crouse looks at the experiences of women hobos in this section of her book The Homeless Transient in the Great Depression:

Hopeless Reimantic Part 1: Virginal Heroines

For more about this series on Romance Novel Tropes, read Rei’s Hopeless Reimantic intro post.

“You were a virgin, Jess.”

“Yes.” This time she didn’t deny it. “And the reason I was still a virgin was because you’re the only man I’ve ever wanted. I was never interested in anyone else. Even when I thought I hated you, I still didn’t want anyone else.”

– Bought: Destitute Yet Defiant, Sarah Morgan (Harlequin Mills & Boon Ltd, 2010)

I pretty much picked that first reference at random. Bought was the first Mills & Boon I ever actually purchased (I say purchased; at the time of writing it was still a free download on Amazon) and it was absolutely everything I thought a contemporary romance would be, so it holds a special, slightly nauseated place in my heart. It was a lucky choice, though, because a great deal of what I want to say about this trope is contained in this book.

The virginal heroine trope is one that holds a great deal of interest for me. Bought is a pretty straightforward example of it – the heroine is a virgin who has never had eyes for anybody but the hero (and she’s twenty-two when the story takes place, taking this out of the believable realm of the adolescent crush), so not only is a sexual relationship with him her first experience of sex, it’s her first experience of emotional intimacy as well – and there’s no mention throughout the book of her having any other friends, so her connection to him is pretty much her only in this world. Not even Fifty Shades of Grey, with its asexual-at-the-start heroine, sets the trope up so perfectly. (Yes, I have read the Fifty Shades trilogy. No, I’m not ready to talk about it yet.)There’s a lot of – entirely justifiable – outrage over how prevalent the virgin heroine is, even today. I am not going to go into the whole problematic mess that is the idea that a woman’s ability to love truly and purely is somehow connected to her physical “purity”, or the idea that a woman can only give herself fully to a lover – as if that’s a healthy focal point for a relationship anyway – if she’s unclaimed territory when the book begins, so to speak. (You would not believe how many romances I’ve beat myself over the head with in which the hero cries “I can’t take this anymore! I don’t care if you were a dirty slutty hobag before we fell in love! I love you anyway! …wait, you were a virgin? OH THANK GOD YOU BELONG ONLY TO ME NOW”.)

This’d be pretty much the standard response to non-virgins in many romance novels. Source: Smart Bitches Trashy Books, link at end of post

Nor am I going to touch on the huge double standard that is the the common pairing of the virginal heroine with the Virile Manly Man, who has explored delightful bedroom adventures with many a lady fair – but still takes the heroine’s virginity as proof that she’s someone special. (But of course has nevertheless been totally respectful of all of his previous partners. Of course.) I may write about them sometime, but this is an overview with a word limit, so I’ll put some further reading links at the bottom of the post and we can call it even for now.

She spans all genres, does the virginal heroine (insert your own pun here. Yes, I said insert. No, I didn’t mean – look, just go and sit in the corner, okay?), and some are easier to deal with than others. The historical probably has the most easily explicable virgin heroine of all; it’s history! We know what women were like in history! Virgins were the most highly prized of all the ladies, weren’t they? Non-virgins were cast out and shunned and other antisocial-type punishments as well, and they would never marry, so any heroine worth her salt is going to have to be a virgin, or she’s not going to be good enough for the hero. Duh. It’s historical accuracy! Everybody’s actions always correspond perfectly with prevalent attitudes of the time, didn’t you know that? The paranormal and fantasy genres get away with it pretty easily as well, often with some kind of mystical bond that predestines the two central characters for one another – although that doesn’t necessarily preclude one of the characters having had sexual relations beforehand. Sound like a contradiction? I don’t think it is – more on that in a moment.

Which brings me neatly to the virgin heroine who gives me the most trouble; the contemporary one. This lady can be anyone, you guys. She’s a businesswoman or a hairdresser or a secretary or a recluse. She’s shy, or she’s loud and brash. But she always has this part of her that is…untouched, as it were, and I’ve seen authors who will write themselves around some pretty amazing corners to keep that so. She’s never found the right guy. She’s never experienced sexual desire before, or if she has it’s been fleeting or fumbling enough to ignore – this is overwhelmingly common. Which brings me back to Bought, with its heroine who waited through an entire book for a hero she was never even really sure she wanted, because the true and deep love she felt for him superceded all other possible emotional connections.

In some ways, it’s not just the heroine who gets this. A discussion on I (Heart) Presents brought me this, from an interview with romance author Julia James:

I must say, I’ve done this several times, when the hero, realising the heroine is a virgin, goes to great lengths to ensure her first experience is really special, and, of course, in doing so, makes it really special for himself as well. In a way, she gives him her physical virginity, and in exchange he gives her his emotional virginity.

[Source]

Smart Bitches, Trashy Books has its own epithet for the hero’s “emotional virginity”; they call it his coming into contact with the Magic Hoo-Hah. (The hero’s counterpart for this is the Mighty Wang, if anyone was interested.) The principle is pretty much the same; somehow, during sex, the hero and heroine exchange a piece of each other that nobody’s ever seen or touched before. And, because of the underpinning idea that men are physical creatures where women are emotional ones, that usually translates to the heroine being physically untouched before she meets the hero, and nobody ever having touched His Heart1.

In a lot of ways it is this, more than a heroine’s physical virginity, that worries me about the trope as a whole. Because it’s been occurring to me more and more often than the virginal heroine does not necessarily need to be a virgin, per se; the second most commonly occurring version of this trope that I’ve read, usually in contemporaries, is one in which the heroine has had sex. Not, in most cases, often – maybe once or twice, and always with the man she fancied herself in love with before she met the hero. But she didn’t really enjoy it; it was uncomfortable or even painful, and after that relationship ended she never really thought of doing it again, and she figured she’d never really understand what about it was so much fun.

Even LGBT romance has its own version of this, in the form of the straight-person-turned-gay (rarely if ever is there a story of a straight person turning bi), who had sex – even lots of sex! – with the opposite gender, but never really experienced attraction before meeting their same-sex true love. Which is a plausible enough narrative, in fairness, but loses something in that the true love in question tends to be the only person our straight-turned-gay hero/ine experiences any kind of attraction towards at all.

I’ve seen justifications of this, and I can see why it’s popular. If romance is fantasy-fodder, what creates a more perfect fantasy than two people exploring new emotional ground together so that you, the reader, can vicariously experience all of that awe-struck joy and wonder? You only fall in love for the first time once, after all, and this creates a world in which the first time you experience this all-consuming emotion is also the only time. You wander into this amazing place, all innocence, and you are thrilled and delighted – and then you never have to leave again. What could be more perfect than that?

Okay, who here has witnessed somebody they’re close to fall in love for the second (or third or fourth) time? And – and I’m aware that not everybody does this – who’s also seen them perform this amazing feat of selective memory, where suddenly their past relationships no longer really “count”? Oh, sure, they’ll say, we had some good times, it was fun while it lasted, but it was never really all that – I always knew something was missing. And now I’ve found it, because this – this – is the real thing.

Who’s seen that repeated over and over again through a cycle of partners?

Because watching that happen? That’s the kind of feeling this trope gives me. I want to be happy that this kind of “mine is a love that I’ve never yet loved” tabula rasa brings happiness to people, but – I can’t. It kind of depresses me, if I’m honest. I’m more a believer in there being A One (or more than one One!) than there being The One, but I wasn’t always, and even when I wasn’t I’ve always kind of thought – so what if somebody’s not The One? Do they have to be secondhand? Even in Fantasyland, is it so important that every single other relationship a person has before they meet The One be denigrated like this? Even stories about a person loving again after they’ve lost a partner to death suffer from this kind of “it was never like this before, this person is touching a part of me that has never been touched” thing, bar a very rare few.

There are exceptions to this, of course. I’m desperate to get my hands on A Gentleman Undone by Cecilia Grant, which unfortunately is only out in print, but features a courtesan heroine who actually enjoys sex, even before she meets the hero. I recently read a pretty damned excellent book by Molly O’Keefe called Can’t Buy Me Love, whose hero and heroine are many things, but untouched ain’t one. In LGBT-ish fiction, and incidentally also one of the “very rare few” widower-whose-previous-relationship-meant-quite-a-bloody-lot books, Deirdre Knight’s Butterfly Tattoo has two people loving again without discounting their prior experience. And the hero’s bisexual. Right on.

So that’s Virginal (Emotionally and Physically) Heroines (with the occasional Hero). Next up, I…haven’t actually decided what I’m covering yet! Enjoy the mystery.

Further reading:

- Recap: Virgin Heroines in Harlequin Presents

- Virginity as Shorthand: the virgin and the playboy strike again (ClitLit)

- Virginity Cliches In Romance (Smart Bitches, Trashy Books)

- Anybody ever saying this sentence out loud is required by law to finish it up with a single emo tear. [↩]

Having had a thorough sulk at P.D. James in the previous article, and explained why I didn’t approach Death Comes To Pemberley with entirely charitable feelings, I’d like to turn to the novel itself. This second article may sound as if I’m treating James’ novel as a reading of Pride and Prejudice (or at least “Austenworld”) rather than a novel in its own right. If so, that’s because Death Comes To Pemberley goes out of its way to insist on the connections between itself and the previous work, and the way it claims to develop the characters. So the first twelve pages are taken up with a Prologue entitled “The Bennets of Longbourn” in which we get to wallow comfortably in the aftermath of Pride and Prejudice. It turns out Mary gets married, Mr. Bennet spends a lot of his time in his son-in-law’s library at Pemberley, and Mrs. Bennet prefers to spend time boasting to her friends about Pemberley’s grandeur instead of enjoying its hospitality.

There are some shrewd bits of character work here, but it’s largely working over the plot of the previous novel, and projecting how the new living arrangements will work out. I kept remembering the passage in Donna Tartt’s The Secret History where Richard, away at a party at a friend’s country house, indulges a fantasy:

of living there, of not having to go back ever to asphalt and shopping malls and modular furniture; of living there with Charles and Camilla and Henry and Francis and maybe even Bunny; of no one marrying or going home or getting a job in a town a thousand miles away or doing any of the traitorous things friends do after college; of everything remaining exactly as it was, that instant…

And we all know how that worked out. (If you don’t, give that book a read. Terrific fun.) All the arrangements seem to slot together rather too well, particularly given the conversation in Chapter 32 of P&P about how a woman may be “settled too near her family”, with its blend of Elizabeth’s longing for her own independent life and guilt over whether that involves being ashamed of her family. I think the phrase “fifty miles of good road” is splendidly ambiguous (and recently discovered it’s the name of an Austen fanfiction community.)

And we all know how that worked out. (If you don’t, give that book a read. Terrific fun.) All the arrangements seem to slot together rather too well, particularly given the conversation in Chapter 32 of P&P about how a woman may be “settled too near her family”, with its blend of Elizabeth’s longing for her own independent life and guilt over whether that involves being ashamed of her family. I think the phrase “fifty miles of good road” is splendidly ambiguous (and recently discovered it’s the name of an Austen fanfiction community.)

The first twelve pages feel like a fantasia on Elizabeth and Darcy’s engagement, a calculation of how everything will be alright now that’s settled, and criticisms aside, that immediately locates the book. We’re encouraged to see it as a working out of stories and characters which were present in Pride and Prejudice. There are different ways a novel can derive from, respond to or somehow continue an earlier work, and Death Comes To Pemberley makes it fairly clear that this is will be a close engagement with its primogenitor. Story continues directly onwards: same main character, similar point of view and locations we’ve seen to a certain extent. That sounds a rather mechanical checklist, but since the novel is in a (partially) different genre it’s worth stressing the extent to which it doesn’t advertise a radical departure from the setting and mode of Pride and Prejudice.

Unfortunately, this means that it has a tendency to the line I identified in my previous post, of pointing out important things which Austen missed out. Since Death begins so closely to Pride, when it diverges it feels like a conscious addition to the first novel’s vision of the world. Servants make their appearance as fuller characters, Wollstonecraft is name-checked, and we are made more aware of a Wider World. It wouldn’t be fair to dismiss the whole book on this basis, and it contains a lot of very enjoyable writing and deft plotting, but there are some deeply surprising moments from an author who apparently respects Austen as much as James does.

For example, Elizabeth sits listening to the wind in Pemberley’s chimneys, and is hounded by

an emotion which she had never known before. She thought ‘Here we sit at the beginning of a new century, citizens of the most civilized country in Europe, surrounded by the splendour of its craftsmanship, its art and the books which enshrine its literature, while outside there is another world which wealth and education and privilege can keep from us, a world in which men are as violent and destructive as is the animal world. Perhaps even the most fortunate of us will not be able to ignore it and keep it at bay for ever.’

It’s unclear in the context whether this is a reflection on the French Revolution, social class or simply Elizabeth “growing up”, but it rather takes me aback to be told that she had never realised that there was an unfriendly rapacious world out there. A significant part of Austen’s original novel (as well as other of her works such as Sense and Sensibility) expends an awful lot of time making it clear that social conventions damn women both ways: determining many of their life choices and opportunities if they stay within the limits, and marking them as “fair game” if they step beyond them. Admittedly Austen’s characters are all of a certain class, but a lot of them are almost obsessively aware of the importance of “respectability”. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that this awareness doesn’t stem entirely from docile acceptance of the need to be a “good girl”, and that it involves a strong, if vague, conception of the exploitation and violence which lies beyond that category.

“Ruin” isn’t a pearl-clutching abstraction for Austen heroines. I mention this because her work is so often dismissed from serious consideration by either enthusiasts who want to claim her as a dating expert, or detractors who see her as a silly woman sheltered from the real world. This isn’t an abstract point of how we frame particular historical texts, it’s having consequences right now. I’ve heard an English Master’s student sarcastically brush off the idea that reading Austen would be worthwhile for her “Because I so want to read about women in corsets fainting all over each other and whatever”, and the assumption that books by women about their lives can have only niche value underpins the sneering category of “chick-lit”. It’s a common point of view, though one which ignores facts such as the apparent influence on Austen’s early work of Laclos’ Les Liaisons Dangereuses.

An even more startling piece of Hark, The Wider World comes about halfway through the novel, during a discussion of whether Georgiana Darcy should be sent away from Pemberley whilst the murder is investigated, or be allowed to help in a very minor capacity:

It was then that Alveston intervened. “Forgive me, sir, but I feel I must speak. You discuss what Miss Darcy should do as if she were a child. We have entered the nineteenth century; we do not need to be a disciple of Mrs Wollstonecraft to feel that women should not be denied a voice in matters that concern them. It is some centuries since we accepted that a woman has a soul. Is it not time that we accepted she also has a mind?”

This is so startlingly shoehorned in that I was almost tempted to class it as a joke. The Wollstobomb is so enthusiastically dropped that I assumed it was either a deliberate frivolity or James was setting her own character up. I’m still unsure about what she’s trying to do here: whether Alveston is intended to be an earnest little prig who is interfering in family business, or the voice of change and the coming century. The former seems to imply that feminism is rather unnecessary in a well-ordered country house where the patriarch is a decent fellow, and the latter to imply (once again) that Austen managed to miss the great world outside her village.

A later passage, which has no obvious connection to gender, decided me. Darcy and Colonel Fitzwilliam are discussing a forthcoming trial (whose, I shan’t mention, for fear of spoilerating) and the jury system. On Darcy’s remarking that the jury will be swayed by their own prejudices and the eloquence of the prosecuting counsel, with no chance of appeal, Fitzwilliam replies:

“How can there be? The decision of the jury has always been sacrosanct. What are you proposing, Darcy, a second jury, sworn in to agree or disagree with the first and another jury after that? That would be the ultimate idiocy, and if carried on ad infinitum could presumably result in a foreign court trying English cases. And that would be the end of more than our legal system.”

That sound is the fictional fabric of this novel splitting apart, so loudly that I can’t even hear Fitzwilliam continuing to speak and hoping that before the end of the century a reform might be introduced whereby the defending counsel will also have the right to a concluding speech. This is clearly intended to be a joke, though I’m again not sure what the joke is. Is it a riff on terrible historical novelists who begin sentences with “Are you suggesting that some day in the future…” or a leaden frolic in the same vein as those novelists?

Either way, it seems to make P.D. James’ technique rather clearer in this novel. Whilst apparently continuing Pride and Prejudice, she also seems to be bouncing parts of history off it in an attempt to broaden Austen’s horizons or simply make fun of the original. Though it’s a skilfully written book from one of my favourite crime novelists, it’s an uneasy read. Mainly because it falls now and then into the sort of approaches to Austen which, as I’ve suggested, belittle her art and relegate “women’s writing” to a cross between a diary column and a dating manual.

Death Comes to Pemberley by P.D. James

It’s difficult not to take this book as something of a betrayal. Not of principles or community, but of me personally, and the fact that I’ve always admired P.D. James as someone who really understood Jane Austen. (By which I mean, agreed with me. Naturally.) When I was an undergraduate I went to see P.D. James speak about detective fiction, and she said one of the most brilliant things I have ever heard anyone say about literature. She declared calmly that Austen’s Emma was the most perfect detective novel in the English language. It gave the reader all the information, she argued, in a perfectly fair way and just let them come to exactly the wrong conclusion for themselves. At the twist, you can look back and see where you went wrong, and how obvious the answer was if you’d only thought it through. And then you can read the novel again, enjoying your awareness of the double tracks the story moves along – knowing about the other story half-submerged in the surface narrative, and switching your attention between them when they come into contact.

I loved this statement so much because it showed a respect for Austen as an artist, and a recognition that her works are deliberately crafted and not simply cleverly observed portraits from life or timeless insights into human nature. They’re literary artefacts with their own integrity and internal structures, something which often gets missed by both detractors and enthusiasts. The former castigate her for not including economics, the Napoleonic Wars or shifting models of gender relations, because no one ever stands up in an Austen novel and tells everyone how worried they are about economics, the Napoleonic Wars or shifting models of gender relations. This is treating her like a newspaper, not a novelist, as if it was Austen’s duty to set down the events of the day in order of importance, and by not explicitly tackling the aftermath of the 1789 revolution she has relegated herself to the Lifestyle supplement.

In order to see the economics and politics in the novels, you have to first take them seriously as works of art whose stories and shapes have some sort of weight, not naive diary columns to be discarded if they don’t trumpet their opinions on current affairs. At which point you notice that the legal arrangements which tie up Mr Bennett’s estate in Pride and Prejudice prevent his daughters from inheriting it, meaning that their survival is dependent upon marrying relatively soon, particularly as the eligible young officers of the militia may be posted to another camp at any time. The entire Lydia-Wickham subplot takes place at the intersection between the legal instruments of primogeniture and the troop movements of the Napoleonic Campaigns. But we can only see this if we stop reading the novels as a transparent window onto the period they were written in, and respect them as novels whose internal structures give them meaning.

Exactly the same mistake is made in the opposite direction, I think, by Austen enthusiasts and the outlets of the Dating-Industrial-Complex. The Jane Austen Dating School, Jane Austen’s Guide to Romance: The Regency Rules, The Jane Austen Guide to Living Happily Ever After and all the rest seem to assume that the value of these novels about courtship in the Regency lies in how similar they might be to courtship in the second Elizabethan era. The blurb of one suggests that “we might have just lost touch with the fundamental rules” of dating, and offers “the only relationship guide based on stories that really have stood the test of time…full of concrete advice and wise strategies that illustrate how honesty, self-awareness and forthrightness do win the right man in the end and weed out the losers, playboys and toxic flirts.” For this attitude, Austen was the Monet of prose fiction – only an eye, but my God, what an eye. The novels can offer us nothing but a meticulous copy of reality, which we can superimpose over our own lives and shuffle around the pieces so they match. It lacks a sense that the works might not be porous and amorphous, that we can’t simply dip in and haul up a ladle full of “Austen”, but might have to investigate where that particular ladleful came from and what relation it bore to the bucketful around it. For the dating guides, the stories lack individual integrity and shape, they can just be copied and printed across any surface like a Cath Kidston pattern.

Both attitudes are obviously, as that Tumblr would say, PROBLEMATIC. The first tends to deny that women writers writing about women’s lives can have any significance beyond their literal content. It’s the attitude that provides us with a women’s supplement in newspapers because everything else in the paper is assumed to pertain to men. It reinforces the supposed distinction between a private female sphere, in which dating and clothes are the ruling topics, and a male public sphere where politics and economics takes place. The second underpins the male/female spheres in a slightly different way, encouraging us to think that one of the great female writers is mostly interesting because of what she can tell us about Catching A Man. It takes Austen’s insights into the inequalities of social life and the power imbalances between the genders, and calcifies those inequalities as the fundamental “rules” of dating. More generally, the lack of concern for the specific form of the works seem to risk playing into a long-standing tradition in Western thinking to associate men with “form” and women with “content”. I may be over-reading that last point, but the line from Plato to Augustine to critiques of women’s fiction as interchangeable “slush” provides a definite context for thinking about attitudes to Austen which assume her writing is an undifferentiated and unstructured mass.

P.D. James seemed to be standing out against both these approaches, insisting that books like Emma or Sense and Sensibility deserved respect as consciously crafted artefacts, whose meanings couldn’t be reduced to their surface in either direction. Along with that came a respect for the distinction between “Jane Austen’s world” and the books which Austen wrote – that the novels were neither a photographic copy of Regency life, not were they series of episodes in a world-building project which could be placed end-to-end to produce a fictional universe across which characters could wander. On the contrary, each one had its own concerns and perspective.

Or so I thought. When she wrote Death Comes To Pemberley it seemed that James had displayed the same attitude as the dating guides and the Austen pastiche industry: that her novels could be regarded as creating “Austenworld”, which anyone could stroll in and out of at will. Slightly ironically, it was her comments about Emma as the most perfect detective novel in the language which made me think that writing an actual detective novel set in Pemberley demonstrated a cavalier disdain for the integrity and form of Pride and Prejudice.

- In Part II I’ll discuss Death Comes to Pemberley itself, and the apparently patronising way it treats feminism (someone really does have a speech to the effect of “But have you not heard of a book which has been written by one Wollstonecraft?”) Then, putting my own massive sulk aside, I’ll explore the possibility that the problems are not with the novel’s attitude to feminism, but its attitude to history.

- EDIT: Read Part II of this post!

Lizzie sent us the following update to her recent previous guest post this morning. If you have a guest post brewing in your brain, you know what to do: pitch us at [email protected].

About a month ago I emailed both Sainsburys and Tesco, following it up with tweets, about the gendering of magazines. It seemed wrong that New Scientist, Photography, NME, The Economist and Private Eye sat in ‘Men’s Interests’ sections while women had the 3,738 fashion and beauty mags as well as knitting and cooking mags.

Tesco were the first to respond, telling me via tweet that they were passing this up to central management:

It took a while for anything else to happen, but a week later I got an email from Sainsburys saying that where they were refurbishing or creating a new store, they would cease to gender their magazines.

Fabulous. I mean, I would prefer it if they spent the small amount of money printing new labels for the plastic holders on their magazine racks and replaced them all NOW, but that’s because they have a lot of stores, and seeing this every day still makes my head hurt and fear for young girls who go in and subconsciously learn that science and politics are not for them and that they should concentrate on being pretty while cooking.1

But Tesco still haven’t replied properly. Nothing more except another tweet to BadRep saying management are looking at it. And now, the Everyday Sexism Project (@EverydaySexism on Twitter, and you can also check out the hashtag #everydaysexism) is really helping out – drawing attention to the gendered labels in a local store and retweeting those pressuring @UKTesco to take some form of action.

What would be even better would be for more of us to email them. And while you’re at it, email Sainsburys too and ask them to put their hand in their pocket to start making the changes now, so we don’t have to look at this sexism everyday. It’s just not good enough.

- Ed’s tiny note: Or indeed the boys who learn to compartmentalise “knitting”, for example, as “for girls” – certainly some proud male knitters have commented on this site in the past! [↩]

Adventures in Subcultures: The Bronies

I’m hoping this’ll be the start of an all-new series on Bad Reputation, where I delve into a misunderstood, secretive, or just slightly odd subculture. Today, we’re going to start with bronies.

Origin of Species

Let’s start with a little background.

Once upon a time (1982), in a marketing meeting far, far away (Rhode Island), Hasbro decided to take on the My Little Pony intellectual property. They marketed it pretty much exclusively at girls. The toys were sold with world-shakingly innovative features such as brushable hair and a unique mark on each character’s butt.

The theme continued with a couple of animated series – in which the ponies partook in such riveting activities as going to school and dating – and even a feature film. This was pretty standard stuff for Hasbro, who had long since realised the value of getting kids involved with a cartoon. My Little Pony continued on form, with few variations on the core premise, until 2010.

My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic

Everything changed in 2010. Lauren Faust, animator supreme, was roused from her cryogenic slumber. Her mission: to turn a tedious, gender essentialist franchise into something that would break gender boundaries and interest a whole new generation in animated ponies with magical tattoos.

There’s also the horse porn fanart, but we’ll get onto that later.

Faust lists the things that she hopes to achive with MLP:FiM in her Ms. Magazine article about the issue. To quote –

There are lots of different ways to be a girl.

[…] This show is wonderfully free of “token girl” syndrome, so there is no pressure to shove all the ideals of what we want our daughters to be into one package.

[…] Cartoons for girls don’t have to be a puddle of smooshy, cutesy-wootsy, goody-two-shoeness. Girls like stories with real conflict; girls are smart enough to understand complex plots; girls aren’t as easily frightened as everyone seems to think. Girls are complex human beings, and they can be brave, strong, kind and independent–but they can also be uncertain, awkward, silly, arrogant or stubborn. They shouldn’t have to succumb to pressure to be perfect.

Yes, My Little Pony is riddled with pink, the leader is a Princess instead of a Queen and there probably aren’t enough boys around to portray a realistic society. These decisions were not entirely up to me. It has been a challenge to balance my personal ideals with my bosses’ needs for toy sales and good ratings. […] There is also a need to incorporate fashion play into the show, but only one character is interested in it and she is not a trend follower but a designer who sells her own creations from her own store. We portray her not as a shopaholic but as an artist.

Lauren Faust, I think I love you. And, apparently, I’m not the only one. MLP:FiM gained a fucking enormous audience, across all gender identities. For example, let’s take a look at this video.

;

Just fucking look at it.

Right, good, so what actually IS a Brony?

Wikipedia will know, right?

Brony is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Krzyżanów, within Kutno County, Łódź Voivodeship, in central Poland. It lies approximately 12 kilometres (7 mi) south of Kutno and 40 km (25 mi) north of the regional capital Łódź.

No, probably not. Let’s try Urban Dictionary and ignore anything referring to a sex act or requiring specialist equipment. It might take a while.

A name typically given to the male viewers/fans (whether they are straight, gay, bisexual, etc.) of the My Little Pony show or franchise. They typically do not give in to the hype that males aren’t allowed to enjoy things that may be intended for females.

That’s better. Pretty accurate, too, though I understand that it’s not a gender-specific term (so pay attention to the word ‘typically’ there).

So what do bronies care about? Why are they bronies? I wouldn’t dream of putting uninformed words in their mouths. I went digging for some My Little Pony forums, and put out a little questionnaire via Twitter and Reddit’s /r/mylittlepony.

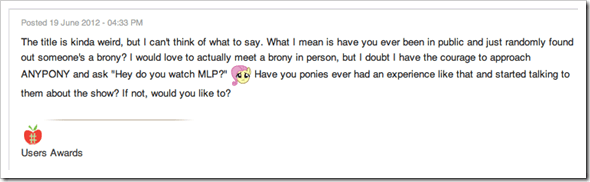

I didn’t have much luck finding any insights on the forums, but I found this post very sweet…

…and this reply absolutely hilarious when taken out of context…

…but I digress. I digress pervily, but it’s definitely digression. Let’s move on to the questionnaire.

The Bronies Speak

“What is your gender identity?”

I discovered after putting the questionnaire online that some female MLP fans call themselves “pegasisters”, so there’s potential selection bias in the results. Still, it validates what I was hoping for – that the majority of responses were coming from the male-identified side of the fandom.1

“Were you a fan of the My Little Pony franchise before Friendship is Magic started?”

The community seems to be nearly exclusively focused on the new iteration of My Little Pony, without any pre-existing interest in the older material.

“Would you be happy for most or all of the people you know to know that you identify as a brony?”

The number of positive responses to this surprised me. MLP fans get a hard time online, and it can only be worse in meatspace. Perhaps the show’s message of love and tolerance results in a more optimistic viewpoint, or attracts those already predisposed to one.

“What appeals to you about the show itself?”

I thoroughly enjoy the idea that a show can be feminine, and ‘made for girls’, without being an overblown, over-prissy tea party. The deconstruction of gender binary and gender stereotypes present in the show is admirable and wonderful.

– anon

It is refreshing to see a show, even amongst children’s programming, that is completely lacking in cynicism. The show and the characters within it are un-selfconciously idealistic and positive. It provides fantastic role models for children of all genders, and the world it has built feels rich and fully occupied.

– Tim (@trivia_lad)

The entire show just feels right. When I’m watching MLP:FiM, it’s like I’m a kid again and I can enjoy the childishness of the entire thing without care.

– Shawn X (@shawnyall)

The character diversity (for once in a children’s show, the fashionable one isn’t the bad guy) and I’m a sucker for the innocent humour included. The characters also have tragic (in the classical sense of the word) flaws: the representative of loyalty is self-centered, the representative of generosity manipulative, and when the representative of Kindness gets mad, even the Hulk would tell her to calm down.

– anon

“What do you dislike or resent about the show itself?”

The vast majority of responses to this question were “nothing, nada, zero”. It seems the community is generally very happy with the show.

It’s a shame Faust had to leave, season 2 was a very different show compared to the first and even though it’s still good something felt like it was missing. I attribute that to Faust’s absence.

– Bret (@the_red_bobcat)

Although strong, not-even-slightly sexualised female role models are a wonderful thing, I am not wholly comfortable with the representation of male characters in the show. With only one or two exceptions, male ponies are represented as stupid, or comic foils, with roles that tend to be service occupations. Unless an episode requires a stallion MacGuffin (See: a Canterlot Wedding, where you get a male character of high social status, though he is very easily manipulated by a strong, evil female character).

– MiaVee (@MiaVee)

“What are you particularly proud of about the brony community? What do you enjoy about being part of it?”

I’m proud of what we do. We start charities, we raise money, we’re so united and loving. Really, I enjoy the love in the brony community. Everyone is just so understanding, caring, and enjoyable. When I first started watching and putting myself into the community, I didn’t know what to expect. But as I opened up more and more, they accepted me without question. They gave my life an entire new part to enjoy, and changed me forever.

– Shawn X (@shawnyall)

I particularly enjoy the community’s openness towards almost every type of person (at least this is true for the Reddit section).

– anon

I am proud of the grown men who are not ashamed of watching a girls’ show just because it is for girls. I like the “love and tolerate” message and the lack of outright trolls.

– Meghan E

I think one of the strongest indications of how the brony community aren’t all creepy, socially inept, hygiene-incapable, sexual predators is the eagerness of the producers and actors on the show to engage with them. The Hub ident produced to promote the second series, a reskin of Katy Perry’s “California Girls” called “Equestria Girls” gives a shout out to bronies, Tara Strong on Twitter actively engages with bronies (as does Andrea Libman, to a smaller extent).

– MiaVee (@MiaVee)

“What negative experiences have you had or known about in the brony community? What would you change if you could?”

The only real negative experience that I’ve known about is the discrimination against a sub-section of bronies called ‘cloppers’ – people who fantasize/look at lewd pictures of characters from the show. The cloppers themselves don’t bother me – it’s the fact that most of the fandom acts like it’s this skeleton in the closet and are extremely ashamed of it, when really it’s not a big deal.

– Rpspartin (@rpspartin)

Anything involving shipping. No no no no no just stop. The show is cute and fine without shoehorning madeup lesbian relationships.

– anon

The only bad times I’ve seen are all the haters that continue to try to bully us. But I wouldn’t change anything. Some of these people just need a friend and we’re more than happy to be that.

– no name provided

Having people approach you and say “My Little Pony? Are you an 8 year old girl?” is part of being a brony, but you can live with it because once you tell them to watch the show it’s an amazing feeling to have that same person come back to you and say “Yeah, sorry bro. That show is amazing!”. Anything that’s rock and roll enough for Andrew W.K. (who’s hosting a “What Would Pinkie Pie Do?” talk) is rock and roll enough for me!

– Bret (@the_red_bobcat)

There is still a lot of misogyny and ableism. Many bronies seem to think that because it’s good, it can’t possibly be for girls, and thus deny that it’s a girls’ show. Alternatively, many get offended when it’s called a girls’ show because they still equate “girly” with ’bad.“ I’d rather seem them embracing the girliness of it, and responding ”yes, it’s for girls, because girls are awesome. Everything for girls should be this awesome.”

– Meghan E.

I’m reluctant to use the term “brony” to describe myself because in every corner of the internet are snarky non-fans seeking to smear every adult fan of the show […] as a fandom overall it seems a lot more welcoming, gentle and understanding than the elitist bullcrap you can get around diehard fangirls and boys for any other show/game/movie.

– MiaVee (@MiaVee)

“Free text time! Tell me whatever you think that I should know. Trivia, gossip, you name it. This is your moment.”

The brony community is huge, and rapidly growing. Like any other community of fans, it is impossible to define the composition, interests, and behavior of its members succinctly. I’d ask, gently, that you please keep this in mind while writing your article.

– anon

I became a slightly more positive and confident person by watching the show.

– anon

All ponies are equal, but some ponies are more equal than others, including Rarity exclusively.

– DocTavia

Rarity is best pony. Anyone who says otherwise is just jealous they aren’t as fabulous

– anon

The only thing I request is that it be made known that Rarity is easily my favourite.

– Bret (@the_red_bobcat)

“The Derpy Controversy”

Derpy Hooves is what’s called a ‘background pony’. She appeared in the crowd in one of the early episodes, and her unusual eyes earned her an instant cult following in the MLP fandom.

Derpy Hooves is what’s called a ‘background pony’. She appeared in the crowd in one of the early episodes, and her unusual eyes earned her an instant cult following in the MLP fandom.

Ever attentive to their fans, Lauren Faust and the rest of the team decided to put Derpy in more prominent positions, and even give her a few lines.

This prompted a few equality-minded fans to complain – ‘derpy’ being a reference to presentations of learning disability. From One Survivor To Another wrote an open letter to Lauren Faust on the issue, and followed up with a smackdown to many of the privilege-tastic counter-arguments that were made.

A modified version of the episode featuring Derpy was released on iTunes with ‘fixed’ eyes; however, the original version was contained in the DVD release.

I’m not going to get into the rights and wrongs of this one here – you can read more about Derpy Hooves’ history on Know Your Meme if you like – but my point is simply that there was discourse in the fandom on the matter. There were strong feelings on both sides, but it’s nice to know that at least the argument could be conducted (mostly) reasonably.

What did we learn?

What, other than the fact that anyone who has expressed a preference wanted to be very vocal about their love for Rarity?

Well, it seems that the MLP fandom are extremely accepting. “Love and tolerance” – a term so popular that I presume it’s from the show – is paramount. We’ve seen this before, in communities like furries and otherkin. Don’t get me wrong – it’s an admirable trait – but it does lend itself to being accepting of the extremes of the community without significantly challenging them. Deserving or undeserving, that’s something that can get a community a bad name in general.

There is an undeniable degree of childish naïveté in the community. Potentially expected due to the nature of the show, it does seem to result in marginalising those who ‘clop’ or enjoy fanart/fanfic of the characters in adult situations. Controversial one, this, and this is only a personal view – but I see it as slightly odd but harmless. The fanart and fanfic are drawn and written, and so they don’t harm any real person. If someone wants to pat their flanks to imaginary ponies in compromising scenarios, it doesn’t harm anyone else.

The community seems to revel in the fact that the production team for the show is interested in what they care about, and are willing to name or give cameos to formerly nameless ‘background ponies’ that gain popularity with their fandom.

Bronies – and the ‘pegasisters’ that I’m sorry to have neglected in the survey – seem to be, on the whole, genuinely lovely people that just so happen to like cartoon ponies. Is their fandom a bit strange? Sure. That said, though, how many fandoms aren’t?

And now, if you don’t mind, I’m going to watch the first few episodes of the first season. It might be terrible – it might be great. What I’m fairly certain of, though, is that it’s not going to piss me off.

- Ed’s tiny note: I’m wondering how our trans* readers may feel about the way we’ve differentiated our categories here. On reflection, it might have been more inclusive to label the “male” and “female” categories “cis”. We did want to avoid any implication that someone who is trans* cannot simply have access to the general terms of “male” or “female” – this is not a view we hold! – but we may not have succeeded, and it’s just as arguable here that we’ve done the opposite. Similarly, the question of whether to involve more or fewer ‘categories’ took some ruminating, and Dave took a while crowdsourcing views on this. In any case, I thought I’d say we’re always happy to receive feedback for future surveys. [↩]

Beginner’s Guide to the Edinburgh Fringe

The Edinburgh Fringe has begun! I’m not there yet – I’ll get there next Saturday – but the Twitter updates from friends there are already making me jealous and nostalgic in almost equal measure. This year will be my fourth Fringe – so here’s a beginner’s guide from – if not an old hand – someone who’s been ’round the Edinburgh block a few times.

Welcome to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival! Wave goodbye to your money, sobriety and any semblance of a normal sleep pattern. Say hello to the weird, the wonderful, and hysterical, dry-heaving laughter of a kind that won’t quite translate to the outside world.

Get ready to start spotting your idols just walking down the street, get ready to say ‘no thanks’ to flyers roughly every 30 seconds, and wind up taking them anyway because the person handing you them was funny/charming/in a funny costume/worryingly eager. Primarily: prepared to be completely overwhelmed for choice.

The very first time I went to the Fringe, I just dipped in for a day when I happened to be in Scotland. My travelling companion and I almost had panic attacks when we started leafing through the Fringe Brochure (about 1/3 the size of a Yellow Pages directory and stuffed full of tempting offers). In the end, we managed three shows in one day, literally ran from one venue to another to make it in time and managed a pretty full Fringe experience: Debbie Does Dallas: the Musical, the wonderful Aussie musical comedy guys Tripod, and a belly-flop of a gig when we paid £10 to see Phill Jupitas Reads Dickens. It was literally just Phill Jupitas reading some of Dickens’ lesser-known short stories and – on that day – he was in a foul mood. Also: the day cost us £45 each in tickets alone. This was before I knew about the Free Fringe (more on that in a moment).

The great thing about the last couple of years when I’ve been up with a show (mostly just doing the flyering for them) is that way you have a big group of mates up there, and you can learn from each other’s viewing mistakes and benefit from each other’s recommendations. There are more shows at Edinburgh than you’ll ever be able to get through, even if you’re there for the full three weeks with both a millionaire’s budget and a jetpack to get from venue to venue – so choosing how to spend your time is important.

Royal Mile

This is where is all happens. The Royal Mile is a cobbled, pedestrianised stretch of road which – for the time of the Fringe – will become a gauntlet of street performers, impromptu performances, and a small forest’s worth of flyers. Shows with cool costumes will be flyering in character, improvisers will be improvising, musicians will be singing, and three small Fringe stages will be showing 10-20 minute showcases from a wide variety of shows.

PBH Free Fringe

The PBH Free Fringe is a wonderful institution. It’s been running since 1996, put together by a guy called Peter Buckley Hill (known to many as PBH.) As the Fringe became more and more expensive, the financial risks increased for performers. While headline names from the telly have guaranteed audiences, the vast majority of performers will be lucky if they break even after a run. As the main groups of venues increased their prices over the years, the financial risks of taking a show up to the Fringe also increased. A debt of a few grand isn’t unheard of, and is easily enough to wipe out a small arts troupe. To counteract this, PBH set up the Free Fringe, where performers don’t pay for the venues and audiences don’t pay to enter.

The PBH Free Fringe is a wonderful institution. It’s been running since 1996, put together by a guy called Peter Buckley Hill (known to many as PBH.) As the Fringe became more and more expensive, the financial risks increased for performers. While headline names from the telly have guaranteed audiences, the vast majority of performers will be lucky if they break even after a run. As the main groups of venues increased their prices over the years, the financial risks of taking a show up to the Fringe also increased. A debt of a few grand isn’t unheard of, and is easily enough to wipe out a small arts troupe. To counteract this, PBH set up the Free Fringe, where performers don’t pay for the venues and audiences don’t pay to enter.

There’s lots of bucket-shaking at the end, but you can see a show and then decide what it’s worth. A good guide: give as many pounds as you would give it stars (out of five). If it sucked – you can just walk out. No obligation. No misgynistic asshole will call. If it rocked your world, give them a fiver (or more!) and buy a book or a CD from the performers. It’s good manners to buy a drink at the venues to make sure they stay with the Free Fringe next year, and to make sure you have enough change at the end. (If you’re broke, you can always just shake the performer’s hand and say thank you.)

Fringe Adventurer’s Cheat Sheet

- Get hold of a PBH Free Fringe guide as soon as you ca.n It lists all the free shows and is arranged by time (not the mind-boggling alphabetic listing of the main programme) so if it’s, say, 3:00 and you want to to see something before your next show at 5:00, it’s easy to flip through and see what’s on.

- Avoid TV names unless you really, really love them. Because their shows are guaranteed to be pricier, and – though it’s not the same – you see them at home on the telly anyway. It’s worth remembering at the Fringe that small audiences don’t necessarily mean bad performances and big audiences don’t mean quality. Go take a punt on something weird and wonderful for cheaps. You might not be able to see it anywhere else.

- Try to get enough sleep. Yes, this runs antithetical to the spirit of the Fringe where there is a constant pressure to do and see everything, and some of the best shows are on late at night, but try to get enough sleep to stay sane, healthy, and up to the task. A couple of times in the past, I’d realise I was finding something intellectually funny but was just too shattered to fully appreciate it. Other times there were slumps and tears. Just… look after yourselves, eh guys?

- Comfortable Shoes. You will be walking up and down a lot of hills, often cobbled, and often in the rain. Get some comfortable footwear, and maybe carry a change of socks to prevent trenchfoot. You don’t want to end up like I did last year, losing a whole afternoon to a trip to A&E to have a swollen, numb, tingly foot looked at. (Nothing broken, luckily, but annoying nonetheless.)

And, finally, recommended shows

These are on my Edinburgh to-do list on account of how I’ve seen the performers (and sometimes whole preview shows) already and I can vouch for their awesomeness. These are arranged alphabetically to avoid having to pick or choose an order:

The Beta Males – The Space Race

The Beta Males – The Space Race

I’ve been a mad fangirl for these guys ever since I saw some little show of theirs in a room above a pub. Huge, howling belly laughs roughly every 10 seconds. These guys are taut, high-energy, dark and twisted, but never go for cheap shots. Blokey without ever straying anywhere near asshat UNILAD territory. Their shows are a series of sketches with an overall plot arc, and their first show I saw – The Bunker – is still quoted in my group of friends with the fanaticism of Monty Python fans. Trailer here. Random awesome YouTube video of theirs here.

Dirty Great Love Story

Dirty Great Love Story

A two-person love story told through poetry. That explanation doesn’t begin to do it justice. It’s heartfelt, down to earth, sometimes awkward, sometimes hilarious, and with polished flows which will make you pause and go “ooooh” until another line brings you back up cackling. Written and performed by spoken word allstars Richard Marsh and Katie Bonna. Trailer here.

Fat Kitten Improv

Fat Kitten Improv

I first saw these guys in 2009 and I’ve been hooked ever since. Full disclosure: they are my mates. Fuller disclosure: they’re my mates ’cause I loved them on stage so much I set about getting to know them. Once reviewed as “well-spoken but batshit insane”. Also they’re a mixed-gender team of predominantly huggable lefty feminists and won’t take cheap shots. Except the odd cock joke. (Hee hee. Cocks.) Improvised comedy will be different every time, so if you like them you can keep coming back and always see something fresh. Shout out your own suggestions and see them acted out for your viewing pleasure. Dance, monkeys, dance! Part of the PBH Free Fringe. Sample here.

Lashings of Ginger Beer Time

Lashings of Ginger Beer Time

Like many things at the Fringe, these guys are hard to pin down – so I’ll go with their own description: “Lashings of Ginger Beer Time is a Queer Feminist Burlesque Collective. Combining songs, dancing, stand-up and sketches, luxe Victoriana drag with thigh-high fetish-boots, upbeat musical theatre optimism with 21st-century political rage, this is music hall for the internet age.” Saw them the other week with fellow BadReppers Jenni, Rhian and Miranda and the show really made me laugh. And cry. Like, lots. *shakes fist* *fails to hold grudge* *hugs Lashings people* Taster vids here.

Loretta Maine

Loretta Maine

Musical Comedy creation of the wonderful Pippa Evans, Loretta Maine is a fucked up Courtney Love-esque singer songwriter. Vulnerability, self-destructive everything, kickass and more than a hint of menace. Her show two years ago, I’m Not Drunk, I Just Need to Talk to You, was a highlight of the Fringe and I’ve had the poster on my wall ever since. Song here. Another one here. Clip of previous show here.

Max and Ivan Are… Con Artists

Max and Ivan Are… Con Artists

Two man high energy sketch duo. They share a lot of awesomes with the Beta Males in their format – minimal, inventive staging, a cast of bizarre characters and a high-energy sketch show with an overall narrative. This year’s one is about a band of assassins, and Max Olesker doing his Joanna-Lumley-posh-voiced character makes me feel funny things in my tummy. Trailer here.

The Mechanisms

The Mechanisms

Musical steampunks in space. “A band of immortal space pirates roaming the universe in the starship Aurora. If you’re very lucky, they might sing you a story before they shoot you.” With a sound defined as ‘Space Folk’ and mad theatrics and kick-ass (feminist!) reworkings of traditional songs and fairy tales. But IN SPACE! Full disclosure: my housemate is in this one. Complete full disclosure: I had to contain my fangirling when I heard their album, because otherwise it could have been awkward. Part of the PBH Free Fringe. Musical preview here.

Other Voices Spoken Word

Other Voices Spoken Word

Oh hai, this is my show. I mentioned it the other week. Put together by the wonderful Fay Roberts and featuring (I’m not just saying this) some of my favourite female performance poets on the scene, I’m chuffed to bits to be part of it. We’ve had some very nice reviews already. Apparently I “delighted the room with poems laced with puns and elegant, elaborate language. By turns comic and poignant, political and surreal, Hannah’s poetry made the audience laugh and made them think, a dangerous combination.” Just sayin’. Part of the PBH Free Fringe.

- The 2012 Fringe runs from 3-27 August.