What Does Feminism Look Like?

Image is important. Sad but true. And it is widely held that feminism has an image problem. I thought I’d do some of my famous research into what the internet says feminism looks like.

This is an exciting web 3.0 INTERACTIVE post, rather than one that’s full of pictures, because of copyright licensing laws. When you hear this noise – *ping!* – click the link and hopefully the search results will open in a new window for you to enjoy.

Google Images

*ping!*

Google provide personalized search results of course, so what you see when you Google images of feminism is probably different from what I’m seeing. But what I got is for the most part old favourites, and mostly images created by or appropriated by the feminist movement. I love these pictures. But they are getting kind of old:

- Rosie the Riveter (what are we going to do when the 1940s aren’t fashionable anymore?)

- “If I had a hammer… I’d SMASH patriarchy” graphic (a proto-Feminist Hulk? SMASH!)

- The female symbol with fist – actually a little alarming when you think about why that symbol represents the female. Punching wombs for equality!

- Various classic slogans on t-shirts, badges and banners

- Pictures of Women’s Liberation marches

- The ‘Look, kitten’ cartoon

- A painting by Artemisia Gentileschi. It’s ‘Judith beheading Holofernes’, in fact. Bet she was a feminist too – we can’t get enough of violence against men, apparently (more on which later)

In amongst these are the anti-feminist blogger’s illustration of choice, the demotivational poster.

Clipart

*ping!*

These days, some people pretend to be dorky to be cool. I’m the real deal. My major love-in with clipart was at secondary school when I decided to make a school newsletter. No one would do it with me, so I wrote and laid it out and printed it and distributed it in all the classrooms by myself. There was no second issue.

Anyway. Clipart offerings for feminism were pretty thin on the ground, and included:

- A burning bra. Sigh. It never happened, you know.

- A woman dressed as a man! Well, in a shirt and a tie.

- That female symbol again.

- A woman with a placard.

- Three women in red – one in a boardroom, one in a boxing ring, and one hefting her male skating partner on high.

Those women in red are just the tip of the iceberg in representations of feminism as women fighting / besting / attacking / murdering men, it turns out…

Stock Photos

Famously bizarre friend of the low budget publication producer, there is nothing quite like browsing cheap stock photography websites. There’s even a tumblr dedicated to some of the more outlandish findings.

Let’s start with iStockPhoto.

*ping!*

Yes, that’s right. The first image to come up under ‘feminism’ is a woman holding a gun to her sleeping partner’s head. See also:

- Tiny man being crushed by enormous womanfoot

- Man being strangled by a woman, Hammer Horror stylee

- Woman with boxing gloves

- Woman delivering K.O. in boxing gloves (live action and cartoon versions)

- Woman standing on a man’s chest in pose of triumph

- Woman treading on a man’s toe in high heels

- Woman unconvincingly kicking a man in the groin

I find this simultaneously worrying, revealing and hilarious. There we were, slogging away, trying to get recognised as a valid and powerful political movement and to assert our credibility as a critical paradigm, and it turns out all the people creating and using these images are afraid that we’re going to come and BEAT THEM UP.

Other things come up too, but the women-attacking-men theme is pretty striking. One notable exception is this unbelieveable piece of tastelessness: “Sexy woman wearing a Burkha”.

On to Shutterstock, a much friendlier and sexier place, it turns out.

*ping!*

There’s really too great a variety of bizarre representations of feminism here for me to summarise, but highlights include:

- One half of a “sexy young couple” smooshing her partner’s face

- “Glamor still life”

- A serene headless phantom feminist

- An old bag

The violence against men is present, but it’s more symbolic – women are cutting or stamping on their ties – or implied: the boxing gloves are back, and this enterprising young lady has an assault rifle.

There are also a lot of pictures of attractive models looking like they can’t wait to advertise your new cleanser.

Not that I could ever afford to buy pictures from Getty, but I checked them too.

*ping!*

Popular themes seem to be men and women glaring at each other in offices, arm wrestling and tugs-of-war (also in offices) and another disturbing guns-in-bed picture.

Last stop:

Creative Commons

Firstly: I love Creative Commons; it basically makes my job possible (producing decent communications materials for charities). Y’all should donate to support them.

*ping!*

Flickr is the main place I use for CC pics, and what comes up under ‘feminism’ is on the whole just pictures of the day-to-day business of it. Panel debates, speakers, meetings, marches, placards, some cool graffiti…

Not especially glamorous, but less weird and less violent than what stock photography sites seem to think goes on. For example, I couldn’t find a single picture of a sexy bride in boxing gloves punching a businessman’s head off.

My model engine has arrived!

Let me tell you about it. It is a simplified, reasonably accurate version of a four-stroke engine, and it comes with its very own Haynes manual. It’s also entirely plastic and aimed at ages 10+. Bollocks, I say. If I had kids that age, I wouldn’t let them anywhere near the thing with their wickedly sharp craft knives. They’d have their fingers off before the first tea break.

Let me back up a bit. A few months ago, I decided that I was going to learn about engines. I’ve always been a bit hazy on the theory behind internal combustion, and despite my father’s repeated attempts to explain, I’ve never really been able to get it straight in my head. This could have something to do with his insistence on explaining over the dinner table, rather than opening up the bonnet of his car and explaining there. (My brother got the lecture over the open bonnet of the car. He got so bored he fell asleep.)

This will all be a lot easier to grasp if I can actually do it myself. If I can take apart an engine and put it back together, you can be reasonably certain that I’ll know how it works afterwards. OK, maybe I’ll explode the back garden a couple of times, but I’ve accepted that as an inevitable consequence.

Miraculously, my new-found zeal is shared by a colleague of mine. She, too, wants to strip down an engine and see what makes it tick. Excellent! We ordered a plastic model to assemble in order to get a vague idea of what it will all involve, before thinking about taking things a little further. While we waited for the model to arrive, we may have become a little… unruly. Rowdy. Noisy. Obnoxious? Surely not!

After one of our exchanges, a colleague came up to me. She works in HR. You know the type: perfect hair, perfect nails, perfect smile. Was my enthusiasm too, er, enthusiastic?

“I just wanted to say, what you’re doing is fantastic,” she murmured quietly, and straightened the strand of pearls at her neck. “I love my car, I’d kill any fucker who so much as touched it. There’s nothing quite like a good engine purring, you know?”

I didn’t know, actually, but I nodded just the same.

The next day, another colleague was delivering some papers over my lunch hour when she saw the driving lessons website open in my browser. “Oh, are you learning to drive? Good for you! I learned in Nairobi, I thought I’d be quite frightened and sedate but it turned out I was a real girl racer, I nearly failed because I was speeding the entire time…”

I’m guessing that speeding will not be encouraged in London.

The next day, colleague Y came up to me, very upset, and drew me away from my desk. “I heard that you and colleague X are rebuilding an engine!” she said, looking very upset. Well, yes. Was this against her ethical beliefs? Was I in trouble with the ‘cycle to work’ initiative?

“Why didn’t you invite me?”

The thing is, I haven’t really mentioned this that much at work, despite being giddy with it for months. The people that have found out about it have either nodded sagely about how many times I’ll set myself on fire, or raved about how brilliant it all is. Invariably, my young female colleagues have fallen into the latter category. They’ve also taken the opportunity to ask me what I thought about the new Pagani (undecided, and I miss the Zonda R), the One-77 (I do like it, but why is it so angry? It looks like it’s been munching on stray pets) and plus, wouldn’t it be nice if the off-road vehicles didn’t kill your spine every time you went off road? (Seriously, Toyota, sort it out.) All of this was delivered in hushed tones over the tea and coffee, and by the time we were back at our desks we were very firmly back on either the Sudan referendum or the receptionist’s new hairstyle.

Why? Was what we were talking about so shocking that it wasn’t fit for general consumption? Would the office spontaneously explode if it turned out that the female accountants and aid workers in my organisation actually knew their Nissans from their Nobles? Why did they get so embarrassed talking about it?

“Well,” colleague X said philosophically, “I didn’t get into cars before because I thought that it was a traditional male thing. And that didn’t mean that I couldn’t do it, but blokes would know more about it than me starting off, and I didn’t want to feel stupid. Then it turned out that they knew just as little as I did.”

Two hours later, a male colleague decided to ask condescendingly what kind of engine we’d be rebuilding. Would it be, he said, sneering, a rotating one?

“A Wankel rotary?” I asked. No. It would be a four-stroke.

- Look out for more Secret Diaries as Vik continues her engine adventure…

Reproductive Justice in the UK: Part 2

Read Part 1 of this article here

I asked some leading UK pro-choice campaigners whether the US reproductive justice approach introduced in Part 1 is relevant to their work, and what – if anything – might be gained from creating a similar movement in Britain.

Shaming black women

Black British women are, according to Department of Health statistics, more likely to have an abortion than their white counterparts (source). On the other side of the Atlantic there has been some especially poisonous anti-choice campaigning based around a similar difference. Georgia Right to Life posted 80 billboards around the city of Atlanta proclaiming “Black people are an endangered species”, with a website address: toomanyaborted.com. Loretta Ross, National Co-ordinator of SisterSong, described it as:

a misogynistic attack to shame-and-blame black women who choose abortion, alleging that we endanger the future of our children… Our opponents used a social responsibility frame to claim that black women have a racial obligation to have more babies – especially black male babies — despite our individual circumstances.

Alarmingly, the UK anti-choice movement has already begun to adopt some of the US campaigning messages about the ‘black genocide’. Lisa Hallgarten, Director of Education for Choice, reported that “the Marie Stopes International clinic in Brixton is routinely picketed by antis who claim that MSI is trying to kill black babies. I have seen leaflets that claim that Brook is a eugenic organisation.” This is just the latest trend in a pattern of UK anti-choicers adopting US campaigning tactics.

Reproductive rights

I wanted to know whether the broader ‘reproductive rights’ approach had been adopted in the UK at all, by which I mean looking at contraception, sex education, adoption and the socioeconomic factors which impact on women’s decisions about whether or not to have children alongside calling for the right to safe, legal abortion.

Darinka Aleksic, Abortion Rights Campaign Co-ordinator, said that “because British women do not experience the extremes of health inequalities on ethnic or economic grounds that women in the US do (although I’m not minimizing those that exist), the repro rights approach has not, in my opinion, been quite so vital or so relevant to our situation.”

Darinka Aleksic, Abortion Rights Campaign Co-ordinator, said that “because British women do not experience the extremes of health inequalities on ethnic or economic grounds that women in the US do (although I’m not minimizing those that exist), the repro rights approach has not, in my opinion, been quite so vital or so relevant to our situation.”

Lisa agreed that a rights-based approach hasn’t been widely adopted: “Since UK policy can be made or broken by the Daily Mail it is hard to take an abstract political or human rights approach to these things”. But she was clear on some of the problems with the existing situation, including the emphasis on abortion as a medical issue:

The public health approach is fundamentally limited and limiting because it relies on scientific evidence supporting the role of abortion in public health. For me there is a point where personal autonomy may trump public health and we should always keep our commitment to autonomy at the forefront of discussion.

And the absence of universal high quality sex education:

Lack of sex education is a clear obstacle not just to the people who are young at that point in time, but to society getting better at talking about sex. I think, realistically, that some fundamental work needs to be done on coming to terms with human sexuality as a society before anyone will have the courage or funding to stand up in government and take a reproductive justice approach to these things.

Abortion rights and social justice

Finally I asked Lisa and Darinka if it would be helpful to put the campaign to protect and extend abortion rights in the UK in a wider context of social justice, and whether there was a risk of losing support in the medical establishment if it came to be seen as a campaigning issue rather than a question of health policy.

Lisa said that:

Our whole law was put in place to medicalise the procedure, put it under doctors’ control and protect doctors. I think there is a big danger of losing their support if they don’t feel ownership of it.

However, the greater danger is that we don’t have a broad grassroots movement to protect abortion rights in this country. If we built a reproductive justice movement we would have a much more broad-based constituency to come out fighting when our rights are up for grabs in the Commons.

Darinka explained that “Abortion Rights’ primary role is to defend the 1967 Abortion Act.” But also that:

As an organization that has strong links to the trade union movement, we are inclined to stress the importance of abortion access as an economic issue. It has always been working class women who have suffered from a lack of access to safe, legal abortion.

Public service and spending cuts are going to hit women hardest and the reorganization of the NHS raises real questions about how access to abortion and contraception services will be maintained. So we are campaigning against the cuts alongside other organizations on a broader social justice basis.

Reproductive justice for the UK?

After talking to Mara, Lisa and Darinka it became clear that there are opportunities for the UK pro-choice movement in the reproductive justice approach, although simply importing the US model wouldn’t work. In Britain public and medical establishment support for the right to choose is far greater, there are fewer differences in access to healthcare along lines of race or sexual orientation, and there is more state support for families.

However, the British sexual and reproductive health landscape is shifting. While the usual attacks on the Abortion Act are being launched in Westminster (and Abortion Rights tirelessly resists them) a few more developments have been added to the mix over the last year – including controversy around the sterilisation of drug addicts and those with severe learning disabilities, the end of the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy, mass popular protests against the Pope’s visit, the crisis in midwifery, and health professionals calling out shoddy sex education in the media.

While there are a whole range of fantastic organizations working variously to defend and extend abortion rights and access, to improve sex education and sexual health, to support families and advance LGBT and women’s rights, to fight racism and inequalities in access to or influence on public services, this work doesn’t take place under a shared banner of Reproductive Justice.

I am a campaigner; I understand the need to choose your battles and your targets carefully. But as the ideological reforms of what is essentially a Tory government start to bite, I wonder if the battle may be coming to us. Perhaps it’s time to build a movement and raise the flag.

- With thanks to Education for Choice, Abortion Rights and the Abortion Support Network: three amazing charities that deserve your support.

Reproductive Justice in the UK: Part 1

I’ll come clean: I missed most of Ladyfest Ten. And I missed it because I was hungover, on about a thimbleful of wine. But one of the things I did actually manage to see that weekend was the excellent US pro-choice documentary The Coat Hanger Project, at a screening organized by Education for Choice.

Towards the end of the film there was a section about the ‘reproductive justice’ movement. The interviews intrigued me. It looked exciting, radical, inclusive and even kinda fun. The film featured an endearing group of smart, funny, young activists that reminded me of the Itty Bitty Titty Committee, which is no bad thing in my book. After a few aspirin I was inspired to find out more…

What is reproductive justice?

Reproductive justice is a holistic, inclusive and intersectional campaign for reproductive rights and the conditions necessary for women to realize them. It is a movement led by women of colour, which addresses the right to have children as well as the right not to have children, expanding the focus out from abortion to include wider questions of sex education, sexuality, birth control and the impact of poverty and violence. This video is a good introduction: What is Reproductive Justice?

And here it is on Wikipedia for good measure.

I had a quick look online for UK reproductive justice groups or networks, but couldn’t find anything, although the US movement has been around since the 1990s. Of course it’s different terrain – here’s an F Word post about some of the differences between the US and UK around abortion and sex education – but is the reproductive justice approach relevant to the UK at all?

Realising reproductive rights

A key aspect of the reproductive justice approach is integrating pro-choice activism into a wider social justice movement. This is from SisterSong’s document ‘Understanding Reproductive Justice’:

Abortion isolated from other social justice/human rights issues neglects issues of economic justice, the environment, immigrants’ rights, disability rights, discrimination based on race and sexual orientation, and a host of other community-centered concerns directly affecting an individual woman’s decision making process.

By shifting the definition of the problem to one of reproductive oppression (the control and exploitation of women, girls, and individuals through our bodies, sexuality, labor, and reproduction) rather than a narrow focus on protecting the legal right to abortion, we are developing a more inclusive vision of how to move forward in building a new movement.

While defending the rights we are lucky enough to have protected by law is vital, the rights become meaningless if people can’t access them, and in many areas social and cultural change and economic equality are needed for people to realise their rights.

How might this be relevant to the UK pro-choice movement? Although abortion has been legal since 1967, and in theory it is freely available on the NHS, there are major inequalities in access. I spoke to Mara Clarke, founder of the Abortion Support Network, who explains some of the problems:

Abortion is available on the NHS, but only if you obtain two doctors’ signatures. This can be difficult if you live in an area with only one GP who is anti-abortion. Access to abortion services can be as much of a postcode lottery as any other service in the UK… This can make things more difficult for women as not only does the procedure become more invasive the further into pregnancy one gets, but not all clinics perform abortions up to the legal limit. This means some women opt to pay privately for abortions to avoid wait times, where other women have to wait until further in pregnancy and/or travel great distances to obtain the care they require.

Thanks to investment and prioritisation by the previous government, things have improved: 94% of abortions are now funded by the NHS, and waiting times have been drastically reduced. However, these achievements, like many others, are likely to be lost as vicious spending cuts unravel years of positive work.

And in both Northern Ireland – despite being part of the UK – and the Republic of Ireland, abortion is illegal except under extremely restricted circumstances. So every year in order to access safe and legal abortion thousands of women are forced to travel to England and pay anywhere between £400 and £2,000 for the cost of the procedure, travel, childcare and time off work. Abortion Support Network works to help these women by providing financial assistance, information, a meal and a safe place to sleep, but they can’t meet the need on their own.

There’s also a major problem around lack of unbiased information and impartial support around sexual health and pregnancy choices for young people, especially about abortion. Many young women are effectively prevented from making an informed decision because they are misinformed at school, or receive biased advice from bogus counselling services. Education for Choice work to make sure young people have the facts, but they are a tiny organisation fighting a wealthy anti-choice movement.

Abortion and race

The reproductive justice movement particularly addresses the experiences and needs of women of colour around sexual health, parenthood, pregnancy and abortion. While there are not such large differences in access to healthcare by ethnicity in Britain as in the US, there are some patterns. For example, according to Department of Health stats, black British women are almost three times more likely to have an abortion than white women (source). It’s not clear why this is, but when I asked Darinka Aleksic, Abortion Rights Campaign Co-ordinator, she suggested an economic explanation:

The argument advanced in the US is that because minority ethnic women are more likely to experience poverty and economic disadvantage, the abortion rate among these communities is therefore higher. The Department of Health in England and Wales does not include income levels in its abortion statistics, but Scotland does, and their figures regularly show that abortion rates are higher in economically disadvantaged areas.

As Darinka points out, there is a similar discrepancy in US abortion statistics, and there’s more in Part 2 about how this is being used by the anti-choice movement in America and starting to be used by our own merry band of anti-choicers.

- With thanks to Education for Choice, Abortion Rights and the Abortion Support Network: three amazing charities that deserve your support.

Come back tomorrow for Part 2

Women in Horror: Five Recommended Writers

As Women in Horror Recognition Month draws to a close, we asked horror author Maura McHugh to tell us about it and give us some reading recommendations. Here’s what she had to say.

If you like scary stories and those who create them, you might be interested to know that February was Women in Horror Recognition Month. This is the second year of the initiative, which was started by Hannah Neurotica out of frustration because of the often-repeated myth that ‘there are no women creating horror’.

While women participate in the horror industry (literature, films, comic books, video games, etc) in fewer numbers than men, they are not absent. Many of them have been working in the field for a very long time, and have considerable credentials. Yet somehow they are rarely remembered and people scratch their heads when trying to recollect their names.

Where women are featured in horror events or magazines there is often an over-emphasis on actresses (Scream Queens and Last Girls) rather than the novelists, screenwriters or directors who are also involved in the field. No doubt this is due to two factors: an over-abundance of male journalists who want to meet their favourite actress, and the usual cultural bias that stresses the value of a woman’s appearance over the strength of her other talents.

No one dismisses the importance of actresses, since women are under-represented in film and television anyway, but women and men deserve more exposure to the variety of work that women accomplish in the field.

Need recommendations?

Here are five of the current crop of female horror writers who are well worth reading.

USA: Sarah Langan

Sarah grew up in Long Island, but went to university in Stephen King territory (Maine), before completing an MFA at Columbia University. After starting to write and publish short stories she graduated quickly onto novels, and in 2006 The Keeper was published to widespread critical acclaim.

Sarah grew up in Long Island, but went to university in Stephen King territory (Maine), before completing an MFA at Columbia University. After starting to write and publish short stories she graduated quickly onto novels, and in 2006 The Keeper was published to widespread critical acclaim.

Since then she has published two more novels, The Missing (2008) and Audrey’s Door (2009), numerous short stories and one audio drama, Is This Seat Taken (2010).

She’s won three Bram Stoker Awards (two for Best Novel, and one for Best Short Fiction), and a Dark Quill Award.

Canada: Gemma Files

Gemma was born in the UK, but moved to Toronto, Canada when she was a year old. She graduated university with a degree in journalism, and began her career with an eight-year tenure at Eye Weekly in Toronto, where she established her reputation as a genre-friendly film critic.

Five of her short stories were adapted for the US/Canadian horror television series, The Hunger (1997-2000), and she wrote the screenplays for the episodes from the second series “Bottle of Smoke” and “The Diarist”. She also taught screenwriting for eleven years. Her short story “The Emperor’s Old Bones”, won the International Horror Guild Award for Best Short Story of 1999. Two collections of her short stories are available: Kissing Carrion (2003) and The Worm in Every Heart (2004).

Five of her short stories were adapted for the US/Canadian horror television series, The Hunger (1997-2000), and she wrote the screenplays for the episodes from the second series “Bottle of Smoke” and “The Diarist”. She also taught screenwriting for eleven years. Her short story “The Emperor’s Old Bones”, won the International Horror Guild Award for Best Short Story of 1999. Two collections of her short stories are available: Kissing Carrion (2003) and The Worm in Every Heart (2004).

Gemma’s first novel, A Book Of Tongues (2010), the first book in her Hexslinger series, won the 2010 Black Quill award for “Best Small Press Chill” (both Editors’ and Readers’ Choice) from Dark Scribe Magazine. The sequel, A Rope of Thorns, is due in May 2011.

Australia: Kaaron Warren

Kaaron was born in Australia, and after a sojourn in Fiji has returned to Canberra, Australia. Her horror short fiction has been gaining attention since she was first published in the early 1990s. She’s now had over 70 stories published in a variety of venues, and has two collections in print: The Grinding House (2005) and Dead Sea Fruit (2010).

Her debut novel Slights (2009), was published to much attention due to its disturbing premise and gripping prose style, and she followed it quickly with Walking the Tree (2010) and Mistification (2011).

Her debut novel Slights (2009), was published to much attention due to its disturbing premise and gripping prose style, and she followed it quickly with Walking the Tree (2010) and Mistification (2011).

In 1999 she won the Aurealis Award for best horror short story, and in 2006 she won the Ditmar Award for Best Short Story and Best Novella/Novelette. She also bagged the 2006 ACT Writing and Publishing Award for best fiction. In 2010 she won a Ditmar Award again, this time for Best Novel for Slights.

UK: Sarah Pinborough

Sarah was born in Buckinghamshire, and she spent her early childhood travelling in the Middle East because of her father’s career as a diplomat. After college she worked as a teacher before becoming a full time writer.

She’s published six horror novels with Leisure Books – The Hidden (2004), The Reckoning (2005), Breeding Ground (2006), The Taken (2007), Tower Hill (2008), Feeding Ground (2009) – and a tie-in novel for the Torchwood TV franchise, Torchwood: Into The Silence (2009).

Her futuristic horror crime novel, A Matter of Blood, the first of her Dog-Faced Gods trilogy, was released in March 2010. She is also publishing a Young Adult fantasy trilogy called The Nowhere Chronicles under the name of Sarah Silverwood. The first book in the series, The Double-Edged Sword, was published last year.

Her futuristic horror crime novel, A Matter of Blood, the first of her Dog-Faced Gods trilogy, was released in March 2010. She is also publishing a Young Adult fantasy trilogy called The Nowhere Chronicles under the name of Sarah Silverwood. The first book in the series, The Double-Edged Sword, was published last year.

Her story The Language of Dying won the 2010 British Fantasy Award for Best Novella.

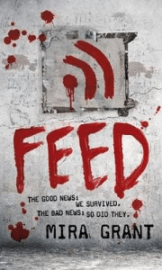

USA: Mira Grant

Mira is the pen name of the multi-talented writer/illustrator/composer/singer Seanan McGuire, who is the author of the October Daye and InCryptid series of urban fantasy novels.

Last year her zombie horror novel, Feed, written as Mira Grant, was published to considerable popularity. The sequel, Deadline, is due out in May 2011, and her Newsflesh trilogy will be rounded up with the publication of Blackout next year.

Seanan was the winner of the 2010 John W Campbell Award for Best New Writer, and Feed was named as one of Publishers Weekly‘s Best Books of 2010.

Seanan was the winner of the 2010 John W Campbell Award for Best New Writer, and Feed was named as one of Publishers Weekly‘s Best Books of 2010.

It’s difficult to pick five out of such a talented field, so I feel obliged to list a number of other writers people should read: Lisa Morton, Margo Lanagan, Tananarive Due, Caitlin R Kiernan, Sara Gen, Lisa Tuttle, Kathe Koja, Joyce Carol Oates, Nancy Holder, Catherynne M Valente, Holly Black, Yvonne Navarro, Lisa Mannetti, Tanith Lee, Lucy Snyder, Marjorie Liu, M Rickert, Mary SanGiovanni, Pat Cadigan, Melanie Tem and Helen Oyeyemi.

We should also give a hat-tip to a representation of the women editors (some of whom are also writers) in horror, such as Ellen Datlow (Darkness: Two Decades of Modern Horror, Best Horror of the Year 2), Ann VanderMeer (Weird Tales), Heidi Martinuzzi (editor-in-chief of FanGirlTastic.com), Barbara Roden (All Hallows, At Ease with the Dead, co-edited with Christopher Roden), Paula Guran (Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror), Nancy Kilpatrick (Evolve, Outsiders), Monica S Kuelber (Rue Morgue), Christine Makepeace (Paracinema) and Angela Challis (Australian Dark Fantasy & Horror).

This is just a small sample of the talented women who are writing and editing horror. There are far more, with new writers breaking into the field every day. I take it as a good sign that this year’s longlist for the Bram Stoker Awards included a more diverse list of writers and editors.

Of course, there are also many supportive men in the industry who have published women and promoted their inclusion.

Let’s hope in a few years there will be no need for Women in Horror Recognition Month. For the moment, however, it’s a necessary reminder to strive for a better representation of the diversity of voices in the horror business.

- Maura McHugh has been a horror fan since she could read gory fairy tales and sneakily watch creepy movies without parental intervention. Her work in various media have been published in a number of venues such as Black Static, Shroud Magazine, and The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror. She co-organised the Campaign for Real Fear horror competition last year. Her first graphic novel, Róisín Dubh, is due this summer from Atomic Diner in Ireland.

An Alphabet of Feminism #20: T is for Tea

T

TEA

Make tea, child, said my kind mamma. Sit by me, love, and make tea.

Samuel Richardson, Clarissa (1747)

Ah, the Joke Post comes upon us at last. T is for ‘t’… very droll. I lift a cup to that. But fie! Have we learned nothing on this lexical journey? First and foremost, tea was not always pronounced as we currently say it: when it first appeared in English in 1601 it was ‘taaaaay‘ and often written tay (like the modern French thé, a bit). It is not quite clear when and why the shift to ‘ti’ happened, but, then, few things are as easy to lose sight of as pronunciation (how many people remember that Keats was a Cockney?)

Tea, of course, has the additional complication that it is not an English word (although what is?) – it came from the Dutch thee, in turn from Malay and, eventually, Chinese Amoy dialect: t’e, or the Mandarin ch’a. Woven into the geographical etymology, then, is a legacy of import history: around the mid-seventeenth century we procured our tea from the Dutch, who imported it from Malaysia and, ultimately, China. What exactly were they importing? Why, tea‘s first definition, of course: ‘the leaves of the tea-plant, usually in a dried and prepared state for making the drink’. In this form, tea began with a queen, and quickly became every eighteenth-century Cosmo girl’s first route of seduction.

Brew and Thunder.

But first – the drink. ‘Made by infusing these leaves in boiling water, having a somewhat bitter and aromatic flavour, and acting as a moderate stimulant’ – in this sense, the word tea is first recorded around 1601, so some trendsetters must have been aware of it before the widespread importing of the later seventeenth century, when tea really came into its own: Samuel Pepys tried it in 1660, and a couple of years later it found a celebrity backer in the be-farthingaled shape of the Portuguese queen consort to Charles II, Catherine of Braganza (remember her?). So, in England at least, tea was from the beginning tending towards the female of the species.

Catherine’s tea-drinking was partly to do with Portugal’s colonial links with Asia, but also with her temperament: solemn and pious, she initially had trouble fitting into the Protestant English court and her preference for a ‘moderate stimulant’ over the ales and beers otherwise drunk marked one of many departures. But tea was quickly owning its stimulating qualities and being marketed as a ‘tonic’, a civilized alternative to alcohol capable of soothing aches’n’pains and spurring on mental capacities: a zeitgeist for the intellectual impetus of the early Enlightenment – as against Charles II’s well-known debauchery – and, in fact, a ‘panacea‘:

Hail, Queen of Plants, Pride of Elysian Bow’rs!

How shall we speak thy complicated Powr’s?

Thou wondrous Panacea, to asswage

The Calentures of Youth’s fermenting rage,

And animate the freezing veins of age.Nahum Tate, from Panacea: A Poem Upon Tea (1700)

But what started out as a Portuguese import became a matter of English national identity, and by the next century London’s East India Company had established a monopoly on trade, controlling imports into Britain (and thus, prices), using its extensive trade links with Queen Catherine’s dowry –then-Bombay – and the East Indies, and Asia. It was thus that the English turned not into a nation of coffee drinkers, but to devotees of the ‘Queen of Plants’. And a queen she certainly was, and not entirely distinct from the maternal and oft-secluded Queen Anne, who dramatically reduced the size of the English court and inspired a new fashion for calm domesticity and politeness. Thus, the bustling male-dominated coffee-houses, but also a more feminine fix at home…

Five Leaves Left.

So in 1738 tea came to mean not just some withered leaf, but also an opportunity for socialising! Hurrah! To be precise, tea became ‘a meal or social entertainment at which tea is served; especially an ordinary afternoon or evening meal, at which the usual beverage is tea’. The fact that it could connote an ‘ordinary afternoon meal’ made tea a convenient beverage to offer casual social callers, although it was also, of course, a beverage that demanded a whole host of conspicuous purchases: a full tea-set and the crucial Other Element – sugar. Thus your tea-table represented Britain’s colonial interests off in China and India to the tea-side, and Africa and the East Indies to the sugar-side, with all the attendant horrors of the emergent slave trade conveniently swept under the (Persian) rug.

The conspicuous consumption tea represented was exacerbated by its price: before mass importation in the mid-century had driven costs down, the leaf itself was fixed at so extortionate a price (a bargain in 1680 was 30s a pound) as to necessitate the purchase of a lockable tea-chest, which would become the responsibility first of the lady of the house, and, when age-appropriate, of her daughter. The woman who held the key to the tea-chest was, naturally, also the woman who made the tea – thus ‘Shall I be mother?’, a phrase of uncertain origin. One theory I came across was that it is a Victorian idiom related to the phenomenon of women unable to breastfeed naturally using teapot spouts to convey milk to their infant instead. OH THE SYMBOLISM.

Whatever the phrase’s specific origins, it’s certainly true that from tea‘s domestic beginnings onwards whole family power structures could hang on which woman this ‘mother’ was. Alas, London’s major galleries forbid image reproduction (WAAH), but if you turn to your handouts, you will see this in action. This is the Tyers family: that’s Mr Tyers on the left, and his son just down from one of the universities. His daughter, on the far right, is about to be married (she’s putting her gloves on to go out – out of the door and out of the family). Her role as tea-maker has, in consequence, passed onto her younger sister, who now sits as squarely in the middle of the family portrait as she does in the family sphere. Conversely, in Clarissa, when the heroine angers her parents they sack her from her tea-task and grotesquely divide it up among other family members (“My heart was up at my mouth. I did not know what to do with myself”, she recalls, distraught. I WANTED TO MAKE TEA!).

And she feeds you tea and oranges…

Of course, while assigning the tea-making to your daughter could be a loving gesture of trust, it also pimped her marriageability: it requires a cool head and calm demeanour to remember five-plus milk’n’sugar preferences, judge the strength of the tea and pour it, all the while making small-talk and remaining attentive to your guests. Add to this the weighty responsibility of locking the tea away from thieving servants and you have the management skills of housewifery in miniature. It also showed off physical charms: poise, posture, the elegant turn of a wrist, a beautifully framed bosom. To take this momentarily out of the salon, no respectable punter would get down in an eighteenth-century brothel without first taking tea with the girls: Fanny Hill spends at least as much time drinking tea as (That’s enough – Ed), and, of course, this kind of performative tea-ritual femininity is a mainstay in the professional life of the Japanese geisha.

So, along with its identity as a colonial mainstay in Britain’s trading life, tea in its origins is also something specifically feminine: a kind of Muse inspiring intellectual greatness, a Queen to be worshipped as a symbol of Britain’s health and power, and a key element in the women’s domestic lives. It could be stimulating, relaxing and seductive, but, as would become disastrously clear, it was always political.

NEXT WEEK: U is for Uterus

Unsung Heroes: Mary Seacole

“She gave her aid to all in need

To hungry, sick and cold

Open hand and heart, ready to give

Kind words, and acts, and gold.”– Punch Magazine

Mary Jane Seacole is perhaps somewhat better known than most of those appearing in this series, having been included in Britain’s National Curriculum and featured on postage stamps as part of the National Portrait Gallery’s 150th anniversary. Despite this she stands as a perfect example of the sort of person we’re interested in here: one who went to extraordinary lengths to achieve their goals, facing risks and giving freely of their time and energy, yet without becoming a household name associated with awesomeness. In Seacole’s case this was primarily due to the fact that she’s been overshadowed in popular consciousness by the similarly impressive Florence Nightingale. So, let’s look back to the 19th century and find out a little about the Crimean War’s other famous nurse.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1805, Seacole was exposed to medicine from an early age. Her mother was a ‘doctress’, using Caribbean herbal remedies to treat diseases – chiefly the yellow fever that was endemic in Jamaica at the time – and Seacole followed in her footsteps. Travels throughout the Caribbean and Central America gave her the chance to broaden her knowledge of herbal treatments, and even to perform an autopsy on a victim of cholera in Panama, an experience she described as “decidedly useful”.

Cholera, along with yellow fever, was one of the biggest sources of patients throughout Seacole’s career. An outbreak hit Kingston in 1850, killing over 30,000 Jamaican people, and Seacole played a role in stopping the death toll from rising higher still. She would battle a cholera epidemic again in 1851 whilst visiting Panama, and a yellow fever outbreak upon returning to Jamaica in 1853. During this time she also began treating people surgically as well as herbally, helping victims of knife and gunshot wounds. Whilst her obvious skills earned her a measure of respect, that respect was tinged with both racial and sexual prejudices, often depicting her as someone who was talented “for a woman,” or “for a non-white.” In her autobiography, she remembers an American delivering a speech at a dinner in Panama, who said of her that “if we could bleach her by any means we would […] and thus make her acceptable in any company as she deserves to be.” This attitude quite rightfully incensed her.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the last time Seacole faced issues as a result of discrimination based on her gender or race. The outbreak of the Crimean War brought with it a concurrent outbreak of disease, especially cholera. Disease was soon proving more lethal to troops by far than injury at the hands of the enemy, and word went out about the need for trained medics. Seacole, as we have established, was something of an expert on cholera by this point, and set sail for Britain. She arrived carrying letters of recommendation from Jamaican and Panamanian doctors, and offered her services to the British Army. She was denied an interview, as the British Army were not entirely keen on female medics at the time.

Conditions in the Crimea, however, forced them to reconsider, with public outcry following an exposure in The Times leading them to form a nursing corps, headed up by Florence Nightingale. Seacole applied to join this group and was again rejected. This time, she felt, the rejection was due to her race.

Having run into two different strands of prejudice and having had her services refused twice, did Seacole go home? Did she return to Kingston, where her work would be appreciated, and where her fairly successful business was located? Of course not. There were people that needed helping, and she was an expert in the skills that would help them.

Seacole travelled to Crimea using her own funds, presenting herself at Nightingale’s hospital in Scutari. Once more she was rejected. So she she did what any incredibly determined badass would do: she built her own hospital. She didn’t have proper building materials or the finances to acquire them, so she built the hospital just outside Sevastopol, using salvaged metal, driftwood and packing cases. Because when you’re awesome you don’t let a little thing like not having a hospital or anything but the most rudimentary of construction supplies stand in the way of helping those in need.

Seacole provided treatment for the sick during the mornings, travelling out to the battlefield later in the day to tend to the wounded. This was often done with the battle still raging on; she would treat injured soldiers from both sides whilst under fire. She reportedly asked no payment for her services from those who were too poor to pay, accepting money only from those who could spare it. Despite this, and continuous thefts of her hospital’s supplies, she prospered, becoming a well-known figure amongst the soldiers in Crimea, who called her “Mother Seacole.” When Sevastopol fell during the autumn of 1855 she was the first woman to set foot in the captured city, again bringing supplies and healing to both sides.

Mary's blue plaque, Soho, London. Image by Flickr user Simon Hariyott, shared under a Creative Commons licence.

But following the war, Seacole did not fare well. With the fighting over there was no more need for her hospital, and little profit to be made from selling off the supplies there. Hounded by creditors, she returned to England destitute, having given everything she had to provide care to people who needed it. In return, the public took care of her, with several prominent people donating to a fund for her, encouraged by a plea from Punch magazine.

Following her death in 1881 Seacole’s impressive actions faded from public awareness, forgotten in favour of Nightingale for the larger part of a century. It has only been in the last decade or two that awareness and recognition of her deeds has begun to resurface.

I lingered behind, and stooping down, once more gathered little tufts of grass, and some simple blossoms from above the graves of some who in life had been very kind to me, and I left behind, in exchange, a few tears which were sincere.

A few days latter, and I stood on board a crowded steamer, taking my last look at the shores of the Crimea.

– Mary Seacole

Seacole’s autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole In Many Lands, is freely available from Project Gutenberg here.

- Unsung Heroes: a new series on BadRep spotlighting fascinating people we never learned about at school…

- Guest blogger Rob Mulligan… is a guest no longer! We’ve had such a good response to this series he’s boarded the good ship BadRep on an ongoing basis. Hurrah! He also blogs at Stuttering Demagogue. Stay tuned for future Heroes.

An Alphabet of Feminism #19: S is for Ship

S

SHIP

Q: Why are ships refered to in the female gender?

A: – The only beautiful lines to match a ship would be that of a beautiful woman.

– When we crusty mariners go to sea we want a way to honor our loved ones left on shore.

– Unless the grew is different they name them after girls. Besides they all have issues & a mind of there own. And cost a fortune to keep going.

– Because they are always wet at the bottom!

– Because the are grace full and slander also very majestic. Just like my woman.

– Because we love our boats like our women.

– Because they need handling very very carefully!Yahoo Answers

OK, you got me. My finely-honed research techniques generally begin with asking Google. Believe it or not, this timeless question: ‘why is a ship called “she”?’ seems to have eluded people for quite a while – along with this Yahoo Answers page, I also consulted this tea-towel in a Greenwich gift-shop and asked my old friend, the dictionary. Nary a satisfactory (read: academic) answer. But let this not stop us – onwards!

We know ship is probably Old English (scip) but its ultimate etymology is officially ‘uncertain’. The Online Etymology Dictionary (whence I have had frequent recourse since my alma mater saw fit to strip me of my free OED online access) considers it to be proto-Germanic (skipen), ultimately from ‘skei‘ = ‘to cut, split’ – now, now, let’s not get bawdy in our quest for gendering answers, it’s easily explained as ‘a tree cut out’: Literal, man. This gives us its first meaning, as ‘a large sea-going vessel’, as opposed to a smaller boat. In modern times, this means specifically ‘a vessel having a bowsprit and three masts, each of which consists of a lower top and topgallant mast’.

These may not be specifically gendered, but by the 1550s people were widely referring to an unsailed ship as a maiden and its initial outing as a maiden voyage (an adjectival form of the proto-Germanic magadinom = ‘young womanhood; sexually inexperienced female’). Of course, this was a trend appropriated in the sky-crazy 1960s to apply to aircraft and other heavy vehicles, and it is still widely used today – with many of its superstitions intact (and possibly justified… don’t know if anyone’s heard of RMS Titanic at all?) The word also has figurative uses and associations: ‘ship of the desert‘, meaning ‘a camel’; and a ghostly ‘Guinea ship‘, which is a sailor’s term for a floating medusa.

I always say it’s the uniform Shirley’s fallin’ for…

Ah, sailors. Perhaps I’m generalizing here, but they have not been widely celebrated for their feminist views. Their superstitions on the other hand – well, those are another matter. Along with Fear Of Maiden Voyages, these also include the belief that having a woman on board was unlucky (the sea would get Angry and Wreak Revenge) and that if a bare-footed female crossed your path on your way to sea you should not get on board (let the lads scoff, you weren’t planning on dying anytime soon). Daughters of Eve were to be kept away from maiden ships in particular at all costs: barren women were simply dying to jump over the keel in the name of fertility, with nary a care for the lives of the carpenters and captain they were endangering in the process.

In fact, the closest a woman should ever come to a ship in Days of Yore was in the form of a bare-breasted apparition (get your tits out, love): such visions would calm gales and rough seas – although this one does rather sound like it was made up by a singularly hopeful sailor down the club of a saturday night – and they possibly explain why so many figureheads seem to have mislaid their t-shirts. What’s that you say? Figureheads? These are carved decorations sitting astride the prow, most common on ships between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries (eventually abandoned because they had grown to such a size that they impeded the vessel’s smooth progress). When they were not effigies of naked women, they generally had something to do with the name of the vessel in question, as with London’s replica of the Golden Hind (or indeed the Golden Behind, led by Captain Abdul and his pirate crew in another of my childhood favourites). Their function, then, could be to identify the ship, ward off supernatural danger or simply to look pretty, in a kind of early version of the pin-up page three – in most cases, they probably fulfilled a mixture of these services.

Their relationships with the sailors manning the vessel could vary: they were almost certainly endowed with some kind of spiritual protective power – we must not forget how perilous a sea voyage remained even into the twentieth century – but they were presumably also viewed with all the Manly Affection evidenced in respondents to Yahoo Answers. After all, there’s a reason a sailor has a girl in every port, and a comparative pendant might be that iconic pin-up image of Betty Grable marketed at American GIs in 1943 (or indeed the retro-appeal of Sexy Sailor underwear). The much-underrated XTC exploited this in their eighties-tastic music video for All You Pretty Girls (1984) (which contains the immortal line ‘in my dreams we are rocking in a similar motion’).

…He won’t look so la-di-dah in a suit of dungarees.

But an enjoyable analogue to this tradition is the tobacco-chewing, slang-spouting, landlubber-hating figurehead Saucy Nancy, friend to Worzel Gummidge in Barbara Euphan Todd’s Worzel Gummidge and Saucy Nancy (1947). She introduces herself to John and Susan saying ‘I’m half a lady because I ain’t got no lower half’ (Gummidge considers her a ‘sea-scarecrow’). True to her epithet (used here in saucy‘s first sense, ‘impertinent, rude’), she is also given to spouting vaguely inappropriate sea-shanties at inconvenient times, the most telling of which suggests a lot about the relationship between sailor and figurehead:

Nancy, Nancy, tickle me fancy,

Here we lift again –

Furling jib to a lifting sea

All together, and time by me

Or the girl in the stern my bride to be.

All this has been diversionary (and, mayhap diverting), but where did the ship go? Well, aside from the fact that the figurehead was in many cases working as a synecdoche for the ship itself, it also serves as an illustration of the relationship between the sailor crew and the vessel’s ‘human’ side (which is almost always gendered female).

Sail on, oh Ship of State

However, as of 1675, ship had a further meaning, in figurative ‘application to the state’, an idea that goes back to Plato and Horace as a model of good government. Plato reckoned that a ship, being a complicated technical beast, required a competent ‘philosopher king’ at the helm, to avoid in-fighting and silliness among the crew (which would, inevitably, end in naval disaster). The idea was picked up by Henry Longfellow (1807-1882), but appears elsewhere as a figurative commonplace.

It takes on a literal incarnation in modern times through flagship ocean liners, whose British incarnations are frequently feminized (Queen Mary 1 & 2, Queen Elizabeth 1 & 2). Here it is useful to compare the lexical-historical conception of queens and nannies – as the devoted will remember, the latter acquired a specifically feminine connotation with the fussy behaviour of a state.

So why is a ship gendered female? Well, aside from the sea-faring gender-assumptions (mermaids, bare-breasted apparitions, and perhaps even the traditional association of women and moisture), there is also the fact of seaborne sexual frustration and resultant kind of genial misogyny of what is arguably a proto-pinup tradition. Perhaps the reason I could find no conclusive answer to this question is that each ship is (traditionally) ‘manned’ by a consortium of sailors, all with different senses of humour.

NEXT WEEK: T is for Tea